Lessons:

3. Constructivist epistemology

Home » 7. Research pathway » 71. Discussion

The approach presented throughout this course suggests considering an intelligent system as a cognitive coupling between proactive and reactive components. We seek to design this cognitive coupling to generate a stream of data that represents increasingly intelligent behavior. We summarize this research approach with the following key concept:

Design a cognitive coupling capable of generating an increasingly intelligent stream of activity as it develops.

This research endeavor entails two difficulties: 1) designing an increasingly intelligent developmental cognitive coupling, and 2) analyzing the stream of data that it generates to assess its level of intelligence.

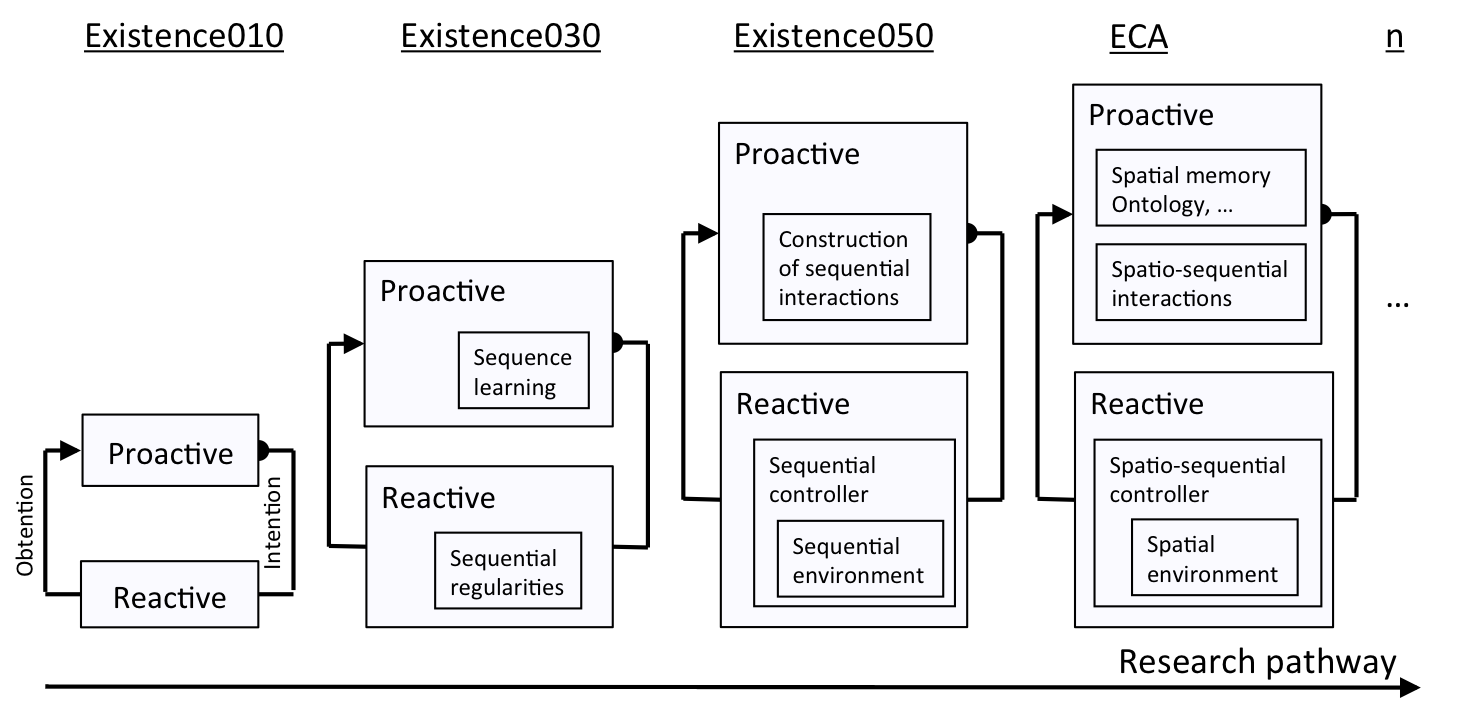

You may have noticed that we have been designing the proactive and reactive components of the cognitive coupling in parallel. Figure 71 recapitulates the progressive improvement of this design over this course.

Figure 71: Pathway to designing increasingly intelligent developmental cognitive couplings.

In Lesson 1, we began with a very simple coupling (Existence010 in Figure 71). We simply illustrated the fact that the proactive part of this coupling (then called the agent) had no direct access to the state of the reactive part (then called the environment).

In Lesson 3, we reached a more complex cognitive coupling (Existence030) in which the reactive part offered simple sequential regularities, and the proactive part discovered, memorized, and exploited these regularities to satisfy inborn preferences. The cognitive coupling and the policy coupling where still superposed: we still considered the proactive component as being the agent and the reactive component as being the environment.

In Lesson 5, the proactive component was able to construct new kinds of intentions (composite interactions) during runtime (Existence050). The reactive component was able to carry out these new kinds of intentions using a function called the Enacter in Figure 53 (renamed as the Sequential Controller in Figure 71). At this point, the distinction between the agent and the environment (policy coupling) no longer coincided with the distinction between the proactive and the reactive components (cognitive coupling). Instead, the agent included both the proactive component and the Sequential Controller element of the reactive component. Also, the environment became only a sub-part of the reactive component (called the Sequential Environment in Figure 71). We were able to connect our agent to the real world (Video 53). However, the agent (a robot) was only able to learn sequential regularities of interaction.

The fact that a single cognitive-coupling cycle spans over several policy-coupling cycles (Page 53)

allows the agent to control different time scales of interaction.

Researchers in artificial intelligence widely acknowledge that this is a critical capacity that developmental agents should have.

For example, Pfeifer & Bongard (2007) in

How the body shapes the way we think?

call this capacity the Time Scale Integration Principle:

"... because sensory-motor processes, which take place in the short term, form the basis of development—which

occurs over ontogenetic time—these different time scales must all be integrated in one and the same agent" (p175).

In Lesson 6, we designed a more sophisticated policy coupling that endowed our agent with an inborn sense of three-dimensional space (ECA, Page 64). This spatial policy coupling allows our agent to autonomously construct rudimentary ontological knowledge. We are, however, still studying how this spatial policy coupling impacts the cognitive coupling. Specifically, we don't know yet how to integrate spatial information into the recursive model presented in Page 52; it is still unclear how higher-level composite interactions can recursively handle the spatial information σt and τt introduced in Page 64.

Overall, cognitive coupling represents the "subjective" viewpoint of the agent. The fact that the environment constitutes only a sub-part of the reactive component allows us to conceive agents capable of carrying out subjective activity, even though they are not actively interacting with the environment. That is, the element of the reactive component that is internal to the agent can generate Obtentions without necessarily involving active interaction with the physical environment. This capacity provides the foundation for internal cognitive activity, which researchers acknowledge as another critical capacity of cognitive systems (e.g., Hesslow's (2002) Conscious thought as simulation of behavior and perception).

After addressing the remaining questions of Lesson 6 presented above, we envision continuing to explore more sophisticated cognitive couplings ("..." in Figure 71). There are multiple possibilities yet to explore, and there is room for multiple research teams to explore different directions in parallel. It will probably require many more developmental-AI enthusiasts like you to make new decisive breakthroughs!

As we presented in this course, we assess the level of intelligence of developmental agents using activity traces. Activity traces may consist of videos that show the agent's behavior. For a more precise analysis, however, we use printed activity traces made of sequential data that represent strips of the agent's activity. This sequential data can include data about the internal state of the proactive and reactive components, as well as elements of the Intentions and Obtentions generated on each interaction cycle.

We submit activity traces to peer reviewers so they can judge the level of intelligence of our agents.

We call this validation paradigm the ethological paradigm.

It is inspired from methods used by ethologists to demonstrate animal intelligence

(e.g., Martin & Bateson's (1993)

Measuring Behaviour: An Introductory Guide).

The ethological paradigm raises the question of defining consensual criteria to judge the extent to which behaviors can be considered cognitive or intelligent. For example, in Video 55, we argue that the emergence of active perception is an indicator of cognitive behaviors. In Video 41, we argue that the fact that different instances of agents develop different strategies to catch prey demonstrates the development of cognitive behaviors.

More generally, the scientific community needs to develop a consensus on the behavioral criteria that the community considers the most important. What kind of behaviors should we observe? What kind of progress should an agent make during its development? Should we observe specific developmental phases? etc. In answering these kinds of questions, the community will clarify what it is trying to achieve when designing developmental agents. We consider this effort of clarification, in itself, to be a contribution to developmental AI.

To contribute to this effort, we have designed a web service tool to analyze and display the activity traces of artificial agents. We used this tool to display the traces in Videos 53 and 63-1. We are happy to share it with people interested in analyzing their agent's behaviors. It is freely available online, and has a user guide to help you personalize the visualization of your traces.

This ends the IDEAL Course. You can continue the discussion in the Developmental AI MOOC community.

See public discussions about this page or start a new discussion by clicking on the Google+ Share button. Please type the #IDEALMOOC071 hashtag in your post: